"The landscape of checkpoint inhibitors in oncology" – part 2! Expanding Approvals, Eligibility, and Response

How many patients are eligible for and respond to checkpoint inhibitors? Here is our eagerly awaited updated analysis, now also including the regulatory context.

Our new paper, titled “How Many People in the US Are Eligible for and Respond to Checkpoint Inhibitors: An Empirical Analysis”, is published today in the International Journal of Cancer (and is fully available here). Let me provide some context and guide you through the main findings of our work.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have changed the landscape of cancer therapy due to their ability to bind and block the action of cancer cells, thus allowing a person’s own immune system to attack and destroy invading cancer cells. This has led to durable responses being produced in cancers that previously had limited response to treatment, namely melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer.

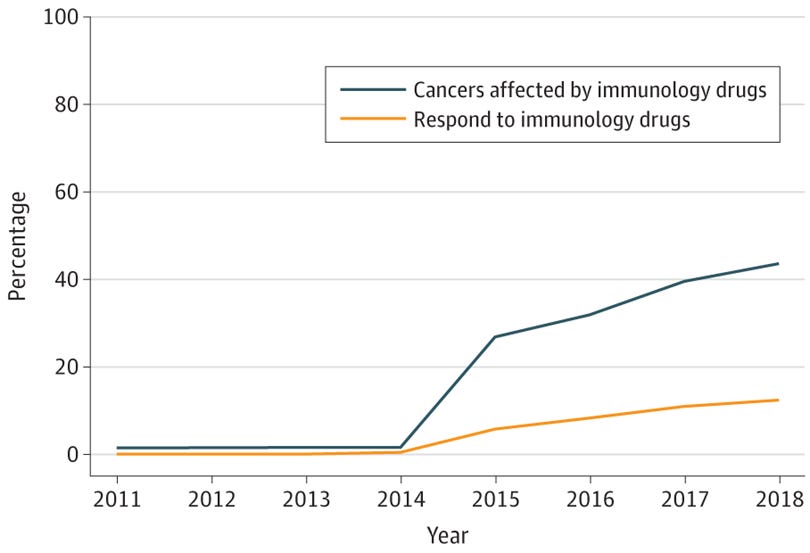

2018 estimates

Early approvals for ICIs were primarily in these tumor types, in addition to others, such as Hodgkin’s lymphoma and urothelial cancer. As of 2018, seven years after the initial ICI approval for melanoma, we estimated that the percentage of US patients with advanced cancer eligible for ICIs had grown from 1.5% to 43.6%, and the percentage of US patients with advanced cancer with a response had grown from 0.14% to 12.5% (see the figure below).

Updated 2023 estimates…with regulatory context

Since then, there have been a number of additional approvals for ICIs, including new drug approvals (e.g., dostarlimab), new mechanisms (e.g., relatlimab, which is an anti-LAG-3), and approvals for tumor types without prior ICI approvals (e.g., triple-negative breast cancer). With these recent approvals, we realized that our first estimates in 2019 needed to be updated, so we set out to do just that. We also were interested to know whether an increase in response mirrored the increase in eligibility that we would likely find.

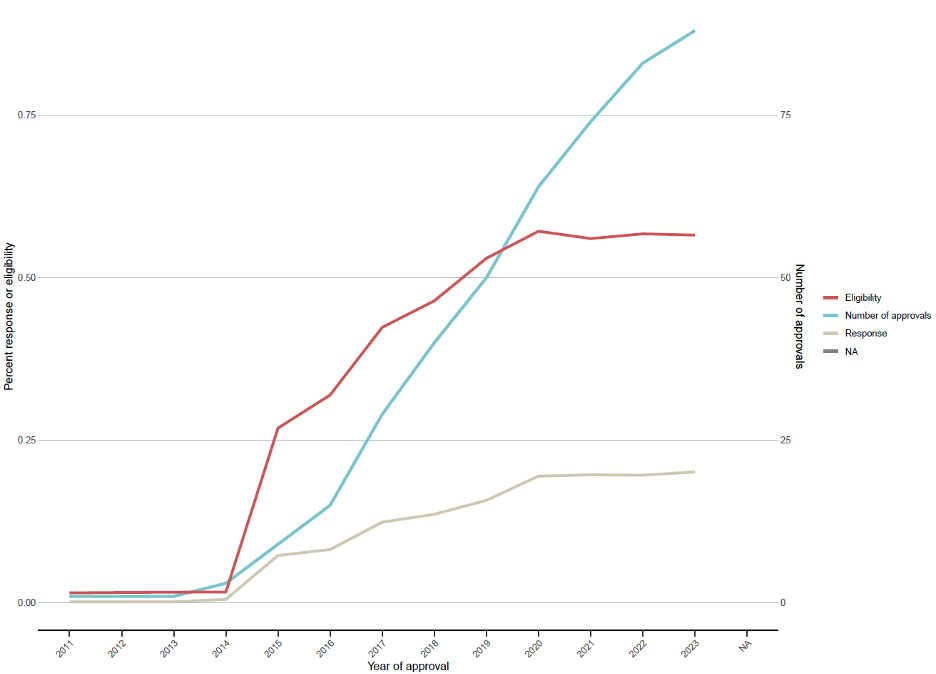

We update our estimates through 2023, and by then eleven ICI drugs had been approved for 88 different indications for 20 general tumor types. In contrast, there were only six ICIs approved for 14 tumor types as of 2018.

In the updated figure, the estimated eligibility in 2023 was 56.4%, and the estimated response was 20.1%. We can also visualize the number of approvals over time for additional context.

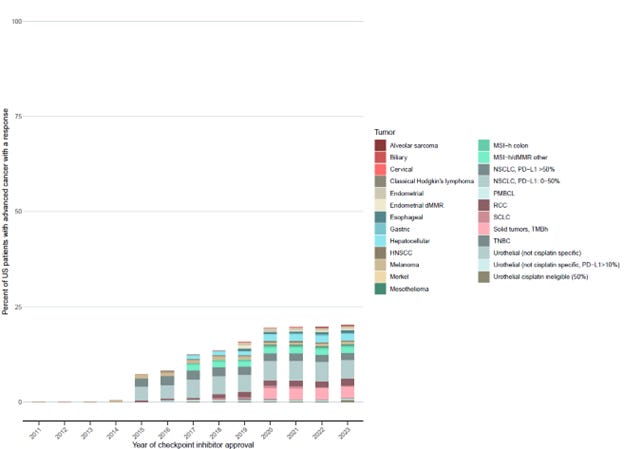

The tumor types that had the highest percentage of people who responded to or were eligible for ICIs were tumor types that had ICI approved prior to 2018, including non-small cell lung cancer and renal cell carcinoma.

Our results suggest that although there have been a number of additional approvals since our first estimates, many approvals have been for tumors with low occurrence and/or have a low response to ICIs. This is indicated by our findings of an 83% increase in the number of ICIs compounds since 2018, versus increases in estimated eligibility and response of only 27% and 61%, respectively.

Who are the patients who respond?

In 2023, the estimated response to ICIs was 20.1% . In Figure 2, we detailed the percentage of patients who respond by tumor type and oncology indications.

Durability of responses

As part of our analysis, we also evaluated durability of responses. We found that only 16 drug approvals had follow-up for at least 10% of patients at 3 years and only 2 had follow-up for at least 10% of patients at 5 years. Of those with patients at risk, the median percentage of patients progression-free at 3- and 5-years was 18.9% and 25.5%. The long-term improvement in response and survival was best for melanoma indications.

We have several thoughts on our findings

First, as more approvals have been granted, a number of them are biomarker specific. This can be a good thing since it allows for therapies being administered to patients who will likely benefit the most. While this may reduce the eligibility to a certain extent, it will be offset by an increase in response. We encourage drug evaluation that uses appropriate subgroup analysis, which puts patient outcomes before maximizing company profits.

Second, while there have been a number of biomarker specific approvals, there have also been a number of approvals for tissue-agnostic indications, which may be less favorable for the patient. TMB-high tumors had one of the highest contributions towards eligibility and response estimates. For our estimates, we assumed that response was evenly distributed across all tumor types with this mutation, but this is likely overestimates response since there is wide variability in responses to ICIs between different TMB-high tumor types. We have previously noted this limitation in drug approvals for tissue agnostic indications.

Third, while this was beyond the scope of our analysis, more approvals are being granted in earlier lines, including in the adjuvant and neoadjuvant setting, which greatly increases the number of people eligible, but the estimates of response are largely unknown, and cannot be assessed in the adjuvant setting by definition, as no disease is visible. The goal of ICI therapy in the metastatic setting is different than in the adjuvant setting, where the tumor has been removed and patients are often cured. Only a few patients benefit, but all patients may experience side-effects, and so many patients may choose to opt out of treatment.

Concluding words

ICI development has greatly altered the landscape of cancer therapy, and many patients have benefited. However, nearly 80% of patients do not respond to them, and 43% are not even eligible to receive them, which indicates that there is still work to be done to determine who benefits most from these therapies, the long-term benefits of them, and how to maximize the benefits, while minimizing side-effects. (Full publication here).

GREAT work! Really looking forward to digging into it! Thank you