One of the most common questions I'm asked is: how do I read this paper? As you know, I've done hundreds of podcasts, and dozens of videos breaking down seminal oncology studies. Here I'll give you a step-by-step guide.

Step one: does the trial have a control arm?

If the trial doesn't have a control arm, you can examine toxicity and measures of drug activity, such the percent of people with 30% or more tumor shrinkage, aka the response rate. Estimates of PFS and OS cannot be compared to anything else, sadly. Some may try to do so, but those analyses are almost always flawed because the study has implicit & explicit inclusion criteria. The patients enrolled are probably destined to do better than historical controls no matter what treatment was given. Smart people know better than to try (see more in Malignant book, Part 3).

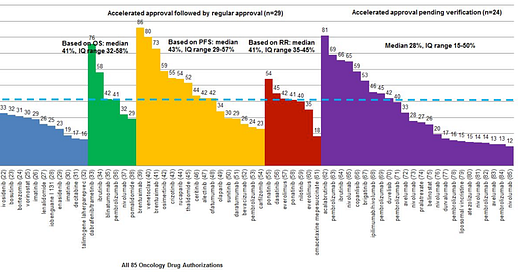

So you're looking at response rate. What are you looking for? Here's a handy table of response rates of drugs approved on the basis of response rate based on our 2019 JAMA IM paper

The first thing I ask myself: is there a drug already in that space? And, if so, is response rate is roughly in the same ballpark? Plus or minus 15 percent is close enough to have strong equipoise. We did that in a 2020 paper.

What does it mean if there is an agent with similar response rate available? It means that you really need a randomized study between the two products. Sometimes you might be surprised how good the response rate is from cytotoxic chemo, and sometimes the RCT might show the older drug is better for clinical endpoints.

Question 2: okay, so, it's randomized; In that case, what's the control arm like?

I always say: A trial can only change your practice if the control arm is your practice. In 2018, now MD Anderson fellow, then OHSU med student Derrick Tao, and I first raised this issue in the Lancet.

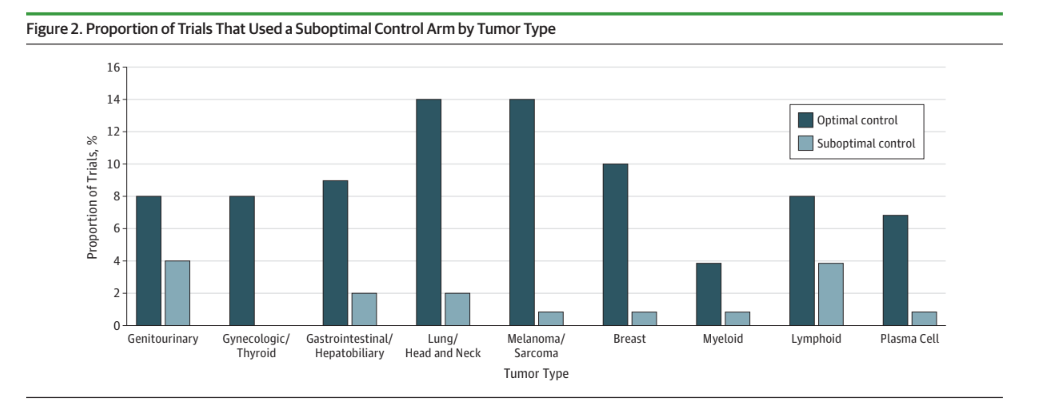

In 2019, Talal Hilal proved that roughly 1 in 5 cancer trials use a flawed control arm. Think POLO, VISION, etc.

A flawed control arm can mean a drug is so bad it should not be used — e.g. POLO. But a flawed control arm can also exist for a drug that probably should have a role— Lu177 PSMA617. In this case VISION cannot tell you when to give the drug, and more work is needed.

Side note: investigator choice is often a limited, and flawed choice, explained in the paper by Olivier.

Question 3: Is the trial adequately powered?

A trial has to be powered for OS (as primary or secondary endpoint) if you want to rely on OS. Same goes for PFS. Griffin is powered for MRD. BR +/- pola is powered for response. Placing too much stock in secondary endpoints for underpowered p2 trials is a fools errand. The worst example of this is olartumab, which had a nearly 1 year OS benefit in phase 2, which evaporated to 0 days in phase 3. Trials are best suited to render verdicts on their adequately powered primary endpoint analysis. Stick to the primary endpoint when you discuss a paper— take secondary endpoints with a grain of salt.

This is explained in my book Malignant in Chapter 11. We also discuss over-powering of trials, which can find a statistically significant but clinically meaningless difference.

Question 4: Was crossover (or post protocol care) used correctly?

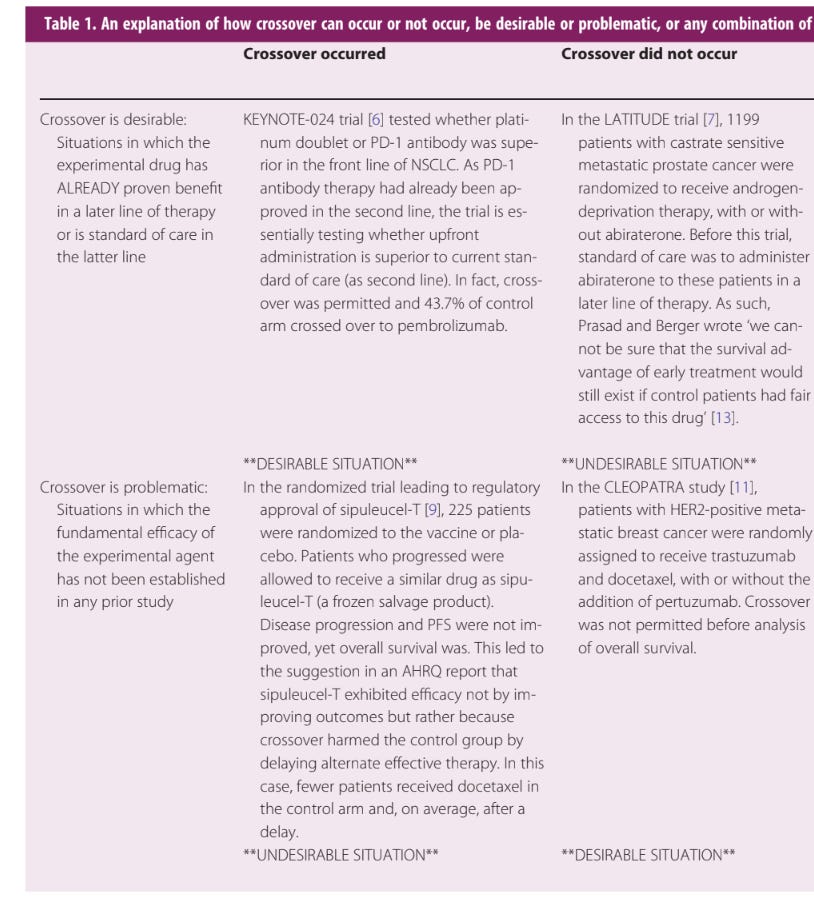

Some trials have crossover and some don’t. Sometimes it is needed, and sometimes it isn’t. This leads to 4 scenarios, and that is why it is confusing. We described this years ago.

In general, crossover is not desirable when you are testing the fundamental efficacy of a drug— think Codebreak 200 or Sip-T— and is desirable if you are testing the sequence of a drug that has already proven benefit— think Keynote 48 or 177.

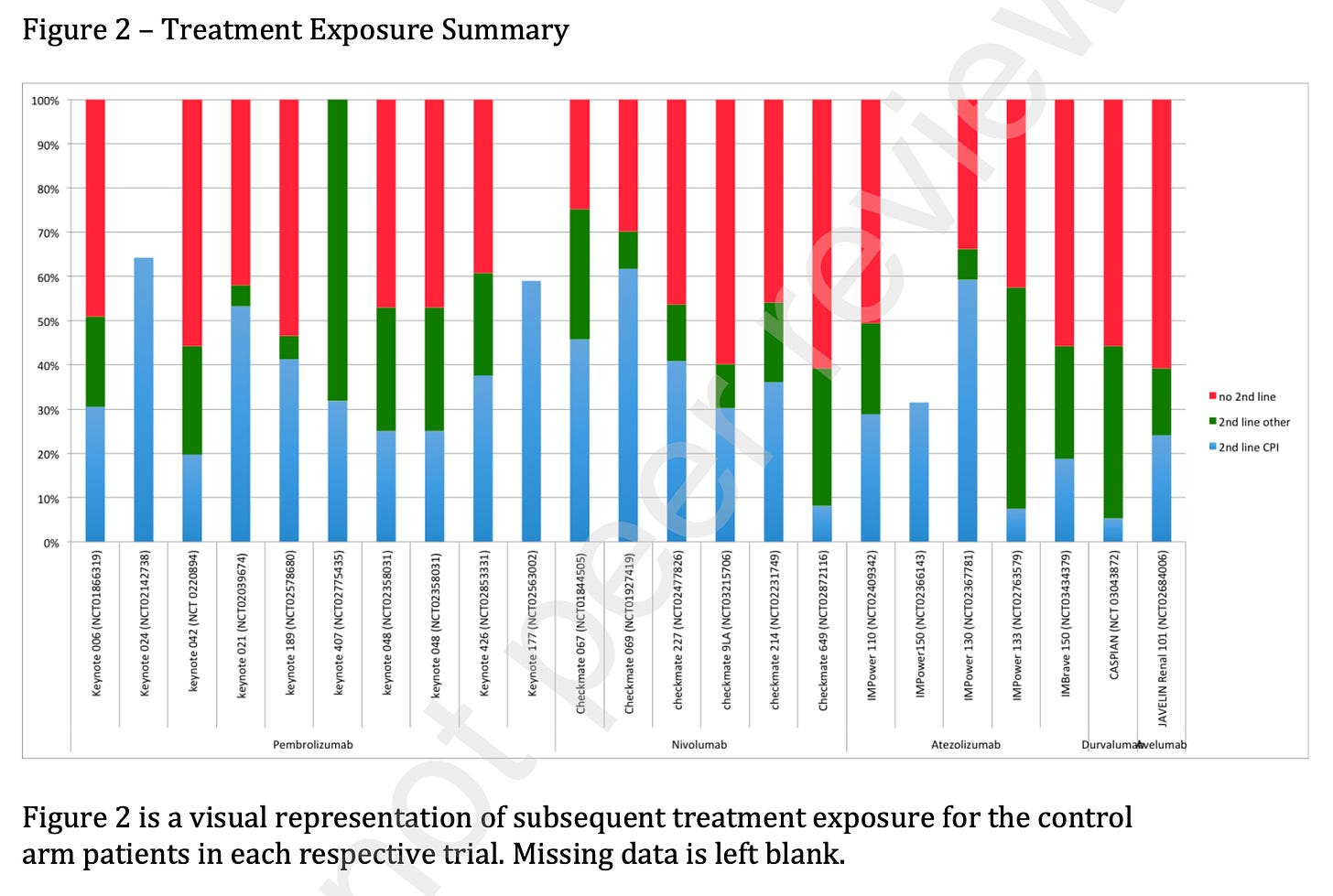

Ashray Maniar, former Columbia University heme-onc fellow, went through all the trials that sought to move up checkpoint inhibitors. This was a situation where the drug had already proven benefit in latter lines, so you want crossover. Here he shows the rate of getting checkpoint inhibitors after progression on the control arm (blue). There should be no green in the figure below, and nearly no red, and yet….

Why does this happen? Companies have every incentive to test the routine upfront use of the costly drug against… never getting it. But this comparison is flawed. I don’t want to know if it is better to get it early vs not at all. I want to know is it better to get it early vs. later.

I explain this concept more in this video (starting 28:15) :

Question 5: What was the endpoint? If it is a surrogate does it have a good correlation with OS?

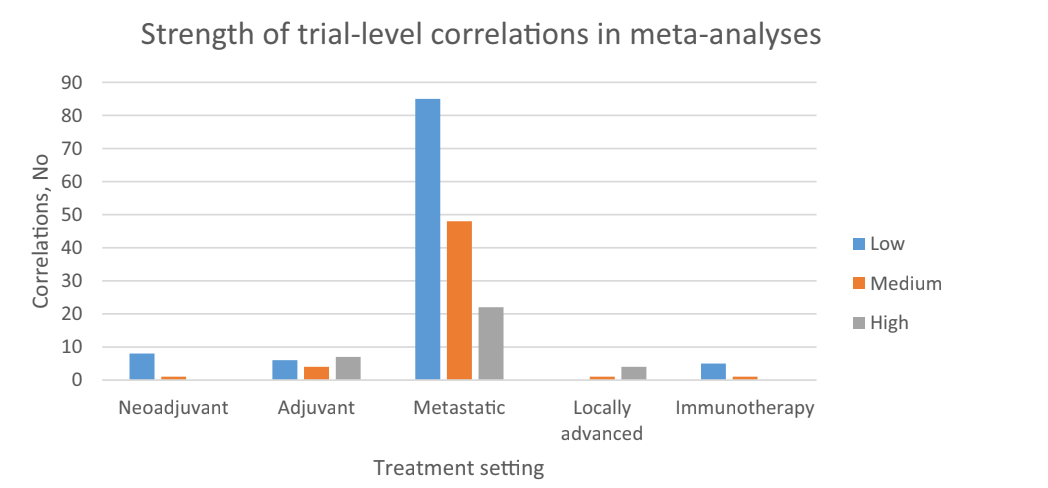

PFS, DFS, EFS. These are all distinct, and I explain them in the video above. Some surrogate endpoints are useful, and some are useless. You need to know the specific correlation with survival. You can rely on them, if the correlation is high in that setting with those classes of agents. Here is what the cancer landscape looks like.

In the link above, we have a table of correlations that have been explored, which will help you. Remember, one cannot extrapolate old correlations to new classes of drugs. For instance, if DFS predicts OS in adjuvant lung with cytotoxic, it might not with IO b/c IO has different properties. Cytotoxics cure in the adjuvant setting, but cannot cure metastatic disease, IO might have durable remissions with both— undermining the correlation!

Question 6: If they measure QoL did they measure it properly?

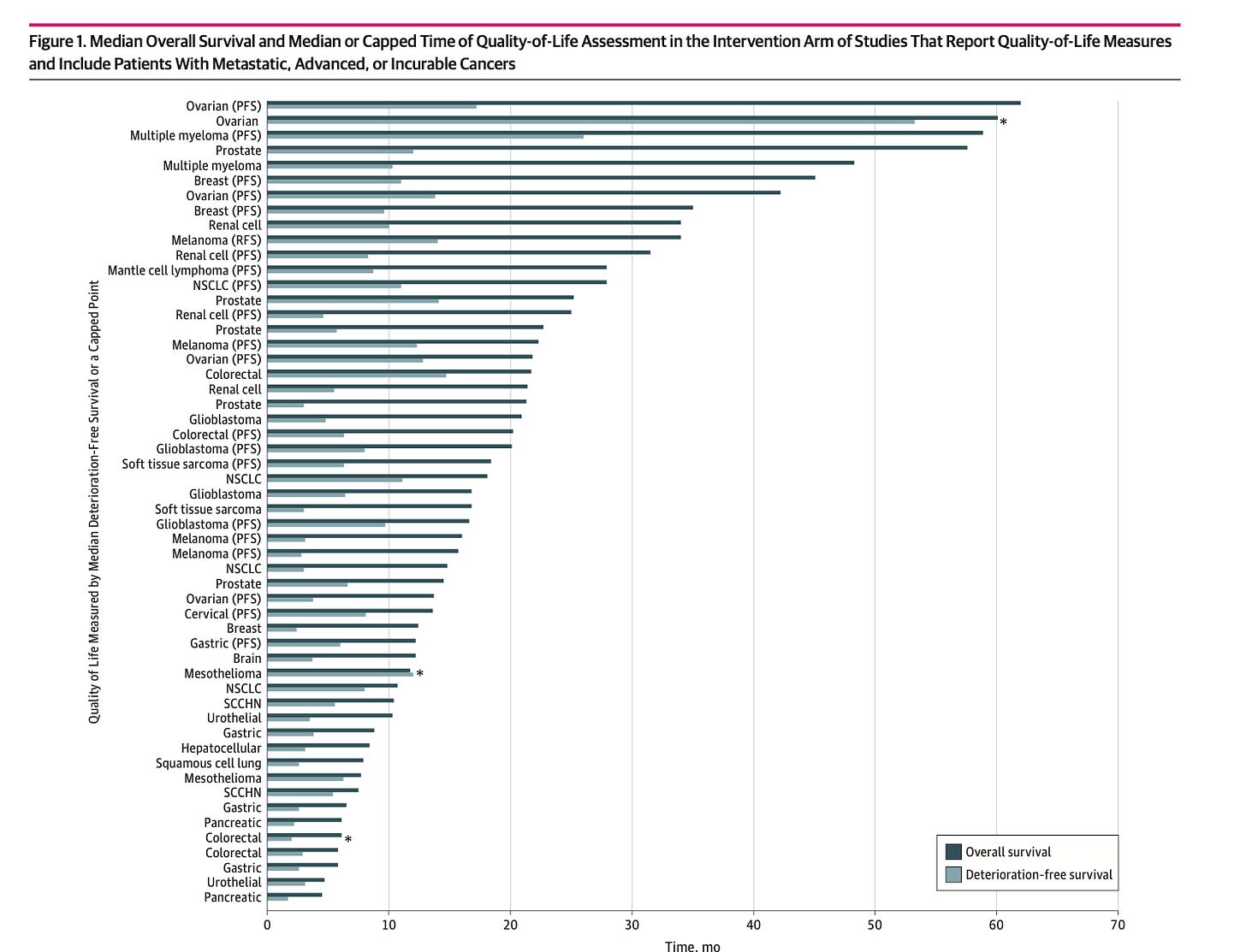

Nothing can be more easily gamed that QoL. It can be full of missing data, and more. The best paper that explains it, is this one by Timothee Olivier.

Previously we asked a simple question: how much of a patient’s journey is captured by QoL metrics. I show that to you here. It is important to judge quality of life by the completeness and duration of the data.

Question 7: Was drug dosing fair?

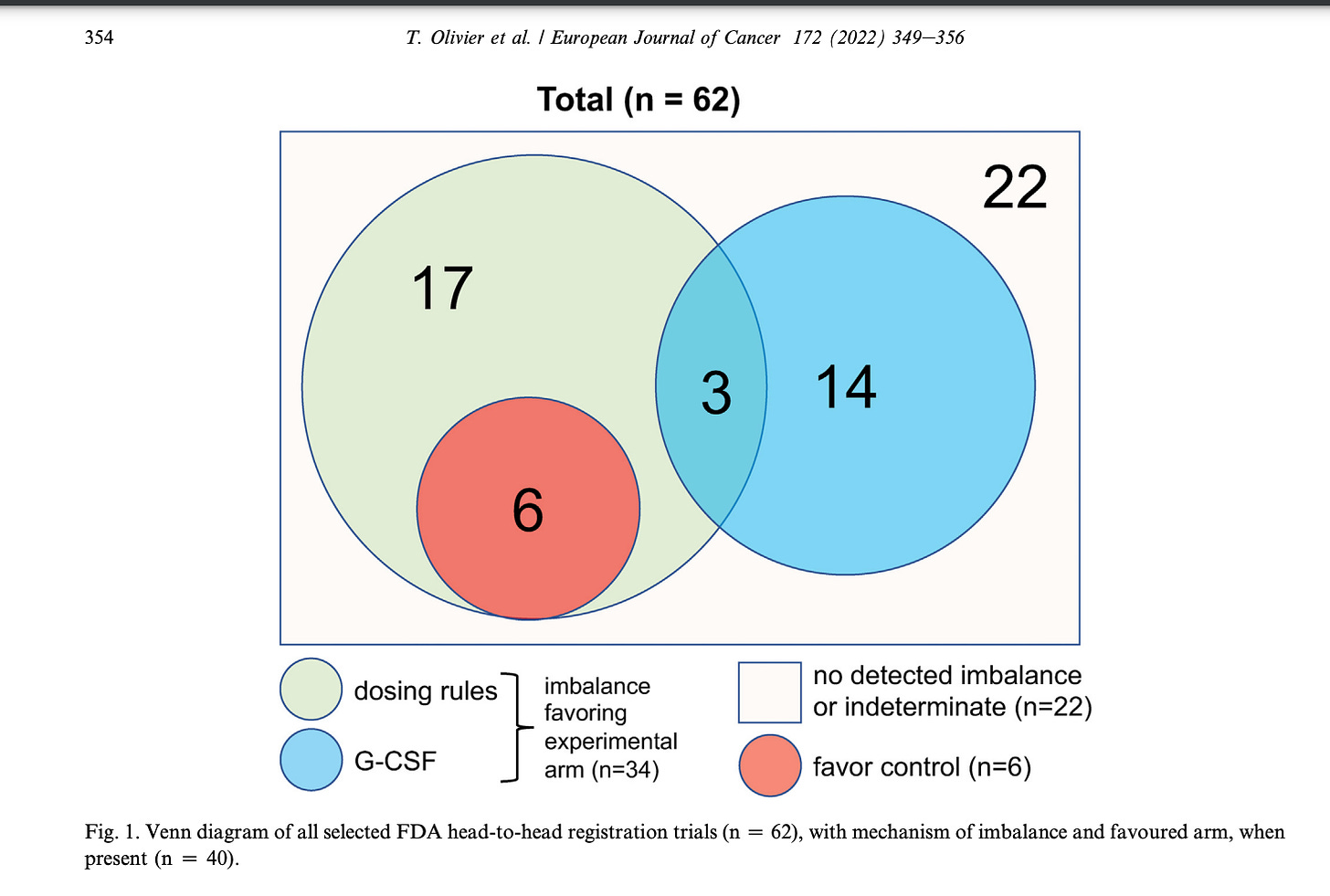

Sometimes the starting dose is fair, but the dose reduction schemes are unequal. Sometimes the new drug gets GCSF support but the old drug does not. Olivier went through dozens of studies to find imbalances in dosing. You should always check to make sure that dose reduction rules and schema are fair. 55% of the time it may be imbalanced.

Question 8: Does the product have value? What is the $$ per QALY

Value is the balance of the benefits of a drug mitigated by toxicity and cost. Once a drug proves it improves survival or quality of life, with the right control arm and appropriate post protocol care, we need to ask what is the value outside the trial— in regular cancer patients.

This means discounting the drug for the fact real world patients do worse. Explained here:

It also means calculating the $$ per QALY fairly. I will write more on this in the future.

Question 9: If it is a non-inferiority trial, I have some special questions.

NI trials are only ethical if a new product is cheaper, less toxic, or less burdensome than the old one. Lenva vs sorafenib in RCC was not an ethical NI trial because lenva is none of those.

The follow up question is: how big is the margin and is that an acceptable loss of efficacy. In the paper above we explore margin size across these studies. If you read an NI trial, read the paper and think about the NI design.

Question 10: You need to develop judgment to render a final verdict

Not all limitations are disqualifying, but some are. How do you know which is which? You need to develop judgement. I try hard on Plenary Session and my Youtube and this blog to teach it to you, but it comes with time.

Reading the book Malignant or listening to the audiobook on your commute will help you immensely. I hope to offer new things to help you more in the future. This judgment of the trial as a whole is the most important thing. It is in part these metrics, but also more than the sum of the parts. Subscribe here to follow along in this journey.

Thank you for all the valuable tips.

As a generalist internal medicine doctor having both inpatient and outpatient practice, I sometimes try to appraise RCTs on oncology about diseases and treatments that relate to patients I see on practice.

But, since they (RCTs) are so many with so many new drugs, it's hard. I think it's the area where I found more difficult to critically appraise the literature. I get mostly stuck on Q2 (++) and Q5. Since I'm not in the field, I don't know from all the infinite publications and RCTs which is the best control arm at the moment. Also, I never know if should rely on surrogates to OS (most of the times I simply don't rely on them).

Do you have some tips to overcome this two main problems?

For Q5 I came to know with this article that you published that systematic review in 2018, which can help. But still, I'll always have to go to the table to look for it and in 5 years some things could have changed.

And for Q2? How can I know the best treatment at the time? A good and reliable source or guideline would be helpful. For guidelines, well, as a generalist, I sometimes have to rely on them. But when I go deeper in the subjects (depending on the society and theme) they're many times flawed...hard times as Dickens wrote!

If the trial doesn't have a control arm it's useless. If it doesn't have a true placebo group, it's useless. If it's control arm is the previous drug this one wants to replace, it is useless. If the trial cites only the RRR or relative risk reduction, it is virtually meaningless.

Then again, in this modern day and age, how do we know that the trial results aren't coming from some chat-gpt program? They feed in the data and like magic chat spits out results giving us a miraculous new cancer drug. I trust no drug trials after the ModRNA substances trial fiasco. But it's fun reading your articles.